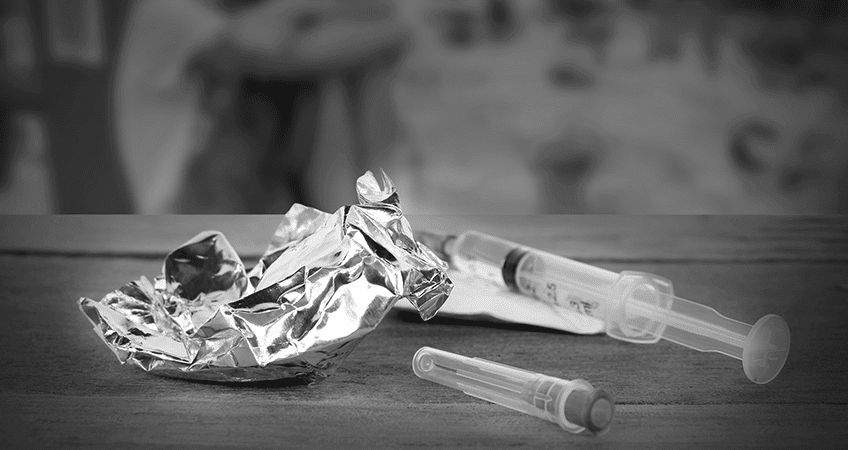

Deciding to stop drinking or using drugs is the first step toward recovery, but the most feared and physically challenging step is detoxification, particular for those abusing opiates. Detoxing from opiates is so challenging that it’s often the reason a person relapses. However with supportive physical and emotional care and by understanding what to expect, detoxification can be successfully accomplished and recovery can begin.

1. Why are opiates so addictive?

Opiates and synthetic opiate-like drugs are substances that latch onto opioid receptors on the surface of certain nerve cells like keys fitting into locks. When drug and receptor connect, the reward circuitry in the midbrain turns on, and there’s a flood of the feel-good brain chemical, dopamine. The dopamine surge creates an intensely pleasurable sensation, a mix of relaxation and elation. In fact, researchers have found that the amount of dopamine resulting from opiate abuse is 2 to 10 times that of naturally rewarding experiences like sex or eating!

- heroin

- Vicodin (hydrocodone + acetaminophen)

- Percocet (oxycodone + acetaminophen)

- Demerol (meperidine)

- Dilaudid (hydromorphone)

- Darvocet (propoxyphene +

acetaminophen) - OxyContin (oxycodone)

- opium

- morphine

- codeine

Over time, the drug-induced euphoria diminishes–less dopamine may be released or the number of dopamine receptors diminishes or both. The person then depends on greater amounts of the opiate to achieve the same degree of euphoria. Eventually, though, a large dose of the drug is needed just to help the person feel normal and avoid withdrawal symptoms.

What’s happened, too, with chronic drug use is that the brain’s centers for learning, memory, judgment, decision-making, and self-control are damaged. Craving for the drug becomes a compulsion overriding everything else in the person’s life. At the same time, the person using opiates is more sensitive to stress, and has increased amounts of the stress hormone, cortisol, circulating in the brain. That contributes further to the compulsion to use opiates. The net effect is addiction, a chronic, relapsing brain disease.

2. What is withdrawal and what does it feel like?

Withdrawal is the response that occurs when the areas of the brain that have been altered by an opiate and dopamine are abruptly deprived of the chemicals.

For example, the symptoms that can be most difficult to cope with are those created by changes at the base of the brain. Normally this area releases a chemical (noradrenaline) that stimulates alertness, breathing, and blood pressure. Opioids put a damper on that activity, leading to slowed breathing, low blood pressure and drowsiness. To compensate for that biological lull, the nerves in the base of the brain put out more noradrenaline. Take away the opioids, and what was just enough noradrenaline for the person to feel normal is now too much, causing anxiety, muscle cramps, and diarrhea.

Opioid receptors are also found in the spinal cord, intestinal tract, and many body organs. So, not surprising, suddenly stopping the flow of opiates has a body-wide impact.

The person may have any combination of symptoms including muscle and joint aches and bone pain and uncontrollable leg movement. Some may suddenly feel cold and shiver and break out in goose bumps or have hot flashes and sweat profusely. Restlessness and feeling agitated can make it hard to be still or go to sleep. The heart may race. Diarrhea, abdominal cramping, and vomiting add to the misery. In short, withdrawal may feel like a bad case of the flu multiplied by 10!

3. How long does withdrawal last?

When withdrawal symptoms begin and how long they last depends on the drug abused and how long it’s been used. Some drugs, such as oxycodone have a short half-life of about 3-4.5 hours. Withdrawal symptoms may occur within a day or two of abstinence. In contrast, methadone has a long half-life of 15-60 hours. Since the drug remains in the methadone user’s body longer, withdrawal occurs later than it does for the person using oxycodone. And the withdrawal will last longer as well.

4. Are there any drugs that ease the discomfort?

Over-the-counter pain relievers may help the aches and pains. And if the restlessness and agitation are severe, prescription muscle relaxants such as Valium may be helpful. However, any prescription drug should be used very cautiously and under a doctor’s supervision so the person does not replace one dependency for another.

5. Is detoxification dangerous?

As intense as the discomfort of withdrawal may be, it is rarely life threatening in people who have no other health conditions. Nevertheless, a person should not attempt to detox alone. Seizures may occur, and some people become extremely anxious or depressed or both. Medical supervision is especially important if a person has a chronic health condition or is simply an older adult who may have an undiagnosed condition.

Being in a detoxification unit of a medical facility or drug treatment center or having someone care for you at home has many advantages, such as helping you stay well hydrated and nourished, offering comforts like warm baths and extra blankets, and providing emotional support and encouragement. It’s also critical that someone be available who knows what to do in an emergency.

After detox

Enduring the physical effects of withdrawal is winning an important battle, but preventing relapse requires long-term treatment. Cravings still occur and it may take months, even years, for brain function to return to normal. That is why we suggest having a plan of action to begin as soon as possible after detox.